In the final part of our streaming series, we look at alternative models and rates and explore the threats and opportunities that AI poses.

Music streaming has long been talked about within the industry in binary terms. Friend or foe; saviour or existential threat; a democratic force for good or a broken system that is in need of fixing. The reality is that it is all these things and more. In this expansive three-part discussion, music and technology expert David Hughes takes us on a deep dive into music streaming, providing an altogether more nuanced look at how it’s changing the industry as we know it. Here are just some of the big questions asked:

- How are streaming services changing the way artists create music?

- Is every stream worth the same?

- What might an AI policy for DSPs might look like?

- What impact is algorithmic inequality having on the overall landscape?

- Can DSPs learn from other industry models, such as Netflix?

- Why does nobody get paid if a track is only streamed for 30 seconds?

Is there the argument that the business of streaming needs to be rebuilt from the ground up? What about alternative models such as the user-centric model?

DH: To explain it briefly for anybody who doesn’t know the user-centric idea is, rather than taking all the money that a Digital Service Provider collects and dividing it according to the total number of plays, they are going to look at what that specific user listened to and try to earmark that money for the artists that they listened to.

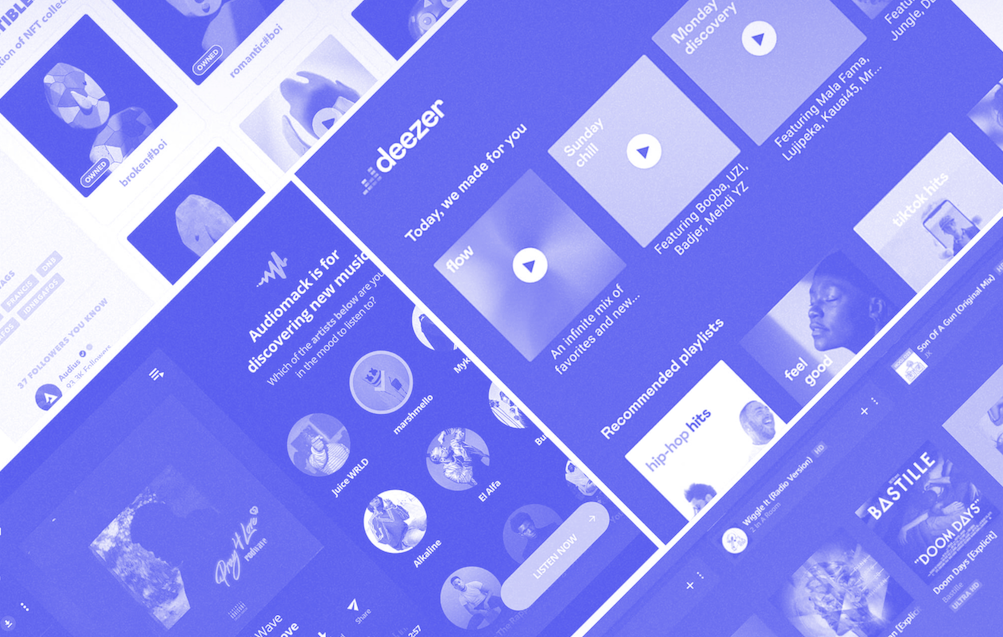

Say I’m paying $10 a month. Out of my $10, $7 is going to go to rightsholders. Now say I only listen to two jazz artists and two singer songwriters. If I don’t listen to anybody else, all my money should go to those four artists and their affiliated songwriters. That’s the idea. It is quite complicated, technically, to do, but not impossible. We have seen Deezer, and others try models in this space. Tidal did their own flavour of this, although it sounds like it was not as successful as they had hoped.

So are there any issues with a user-centric model?

I think what you find is, that as much as people say I’m a big indie fan, I want all my money to go to the indies, even those people spend a significant amount of their time listening to the top 40 artists. And so, in the end, it probably doesn’t rebalance the economics as much as many people would hope.

But the one thing that the industry should keep looking at is the question of how we can create an economic ecosystem that supports non-superstar artists. It’s a challenge, but there are other challenges too, and these are the ones that Lucian Grange and others have been talking about.

People are starting to talk a lot about the challenges and opportunities posed by AI within the streaming world. What are some of the challenges you can see?

DH: What we’re seeing is AI generated music flooding streaming services. Currently, there’s no big disincentive for aggregators like TuneCore and DistroKid – the kind of services where they’re charging the end user a fee to get their money onto the DSPs – to stop putting AI created tracks on streaming services.

Rob Stringer at Sony Music called it the ‘Flotsum and Jetsum problem’ – I think he was specifically talking about do it yourself, amateur hobbyist music that’s clogging the pipes. But it applies to AI created music too. The problem is when third parties syphon money off by interspersing short AI created songs or commissioned songs, that are just good enough that people will listen to them and not skip. Then boom, that money is just being syphoned off and it’s not going to the people who created the music that the listeners came for.

Do services like Spotify need a separate policy for AI music then?

DH: I think even if the only policy was AI content has to be tagged as AI created, that would be a good place to start. But it raises an important question which parallels the conversations that we had in the download space, and that is, is every stream really worth the same? And this is a very interesting argument. When I was at Sony Music and we were negotiating with Apple for the iTunes Store, Steve Jobs decided unilaterally that all songs should be the same price. They should be $0.99 in the US and 99p in the UK to start. And we, of course, made the argument that some song off the B side of the third Boston album does not have the same market value as the latest hit from Destiny’s Child. It just simply does not. You can’t compare Beyonce’s latest hit with some song that’s just a filler song on an album that barely sold anything, and yet he said it has to be 99 cents per song or it’s too confusing for the consumer. That was the argument that Steve Jobs made. What I believe Jobs really wanted to do was just keep prices down so that people could afford to buy more music and then they’d have more incentive to buy iPods.

But we have a parallel argument now. When somebody goes on a DSP and they stream Bruno Mars or Beyonce’s latest hit, should those artists be paid more for that stream than some filler music that we know is not driving the customer to pay the monthly subscription? People are simply not paying $120 a year so that they can stream AI created songs. So now the argument in the negotiations between the majors and the DSPs will probably be, we want a higher streaming rate for songs that are on the charts, or the most streamed tracks on a given service such as Spotify.

How might different streaming rates look in practice?

DH: The labels are going to try to have some kind of scale, I suspect, which is, ‘sure, you can pay us the current rate, but when that song hits a threshold, when it’s been streamed 10 million times, or 100 million times, or it gets streamed a billion times, then the rate should go up a little bit each time because those are the tracks that are driving your subscription business.’ It is for these tracks that people are coming back every day to Apple or Amazon Music, and that’s why they’re coming back every month and paying their subscription fee. I think that’s going to be the argument.

We have started to see this in the press in the past few weeks. People are mentioning this concept right now, but in order to do that, unless they lower the price on the other streams, which I don’t think politically the DSPs could afford to do, they can’t suddenly tell the less streamed artist, hey, you’re only streaming less than 100,000 times, so instead of paying you four tenths of a penny, we’re only going to pay you a quarter of a penny per stream because we need that other money for Drake and Taylor Swift and Adele, but that approach is not going to work. So what they have to do is consider raising subscription prices. So all these things start to come together. There will be pressure for the services to raise prices and the additional revenues may in turn change the way that music is paid for. Now this doesn’t help the hobbyists get more money, but if the threshold is correctly set, and this is important, if the threshold is correctly set, it means that professional musicians who depend on this revenue for their livelihood will get more money.